Hyderabad’s Water Shortage

How Prone is IIIT ?

Pahulpreet Singh

India is facing its most serious water crisis, and the problem is so grievous that even small children are well aware of it. For instance, my 7 year old cousin was worried about why I was going to Hyderabad if it is going to run out of water soon.

Today India ranks 13th in the list of 17 countries where water stress in extremely high – a list that contains countries like Saudi Arabia and the UAE, where large parts of the country are deserts[1]. According to environmentalists, India has only 5 years to solve this problem before things get out of hand. With 80% of the groundwater withdrawn, over 300 million people are affected by severe drought[2]. The challenges of the future that we have been brought up being told about, we are facing those in the endgame now. According to a report by NITI Aayog[3], 21 major cities may run out of groundwater by 2020. And sadly, Hyderabad happens to be one of them.

The factor that is responsible for the majority of this is a delayed start and sluggish progress of monsoon in Telangana, with a 29% drop in average rainfall in Hyderabad[4]. The city primarily gets its water from Nagarjunasagar reservoir (River Krishna) and Yellampalli reservoir (River Godavari), and both of the tanks going through steep drops in water levels raises concern for the citizens.

Despite the magnitude of this problem, the Hyderabad Metropolitan Water Supply and Sewerage Board (HMWSSB) says that there is no cause of concern and expects to tide over. While HMWSSB is looking at mitigation and plans to tackle water crisis one year at a time, Experts have warned that much larger problems loom over the city, which will only get worse with each passing year. It has been suggested that authorities, instead of pumping water from faraway reservoirs, should promote local solutions such as rain-water harvesting and recycling of sewage.

Narrowing down our perspective to the level of our campus, there are two sources from where IIIT gets its water from – HMWSSB and the IIIT borewells. Upon contacting the college authorities, they were kind enough to provide us with some data, so that we can get a clearer picture as to what exactly happens.

In a day 96 Kilolitres of the water used is supplied from HMWSSB while 220 Kilolitres is drawn from 5 functional borewells in the campus. So the borewells play a major role in the water situation as they help us in meeting roughly 70% of our daily water needs. The campus also has three grey water filter beds which recycle 45 Kilolitres of water per day, and this water is used for landscaping purposes. Borewell recharge pits have been constructed by redirecting surface runoff, and terrace runoff from various buildings, to the nearest borewells. A sewage treatment plant of capacity 0.4 MLD (Megalitres per day) is being constructed in the campus, which is expected to be ready for use by February 2020, and the plan is to use the water from this plant for landscaping, and for flushing in the hostel toilets.

Hence we can sleep well knowing that our campus is capable of tackling the problems of the water crisis for a few more years, thanks to the water conservation practices employed including the construction of water storage ponds, rainwater harvesting pits, and borewell recharge pits. However, none of this should take us away from the fact that water is a finite resource, and that we, as students and citizens, should do our part in ensuring the better utilisation and conservation of this all-important resource.

Covering the CAA-NRC Panel Discussion

Covering the CAA-NRC Panel Discussion  Vim Club has its first session !

Vim Club has its first session !  Interhouse Cricket Matches Underway

Interhouse Cricket Matches Underway  IIIT’s Area 51 Raid

IIIT’s Area 51 Raid  Megathon 2019

Megathon 2019  Can you hear the music?

Can you hear the music?  The river of time

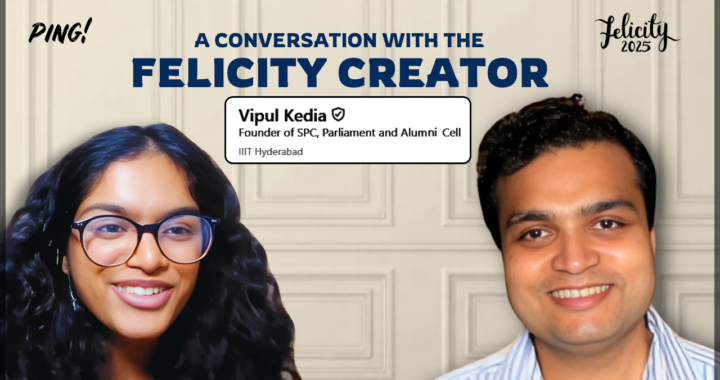

The river of time  Vipul Kedia on building Felicity | The story of how it all began…

Vipul Kedia on building Felicity | The story of how it all began…

1 thought on “Hyderabad’s Water Shortage”

Comments are closed.