The Invisible People Behind OBH

We approached Saraswati*, a lady in her mid-late 20s sitting on the mud ground with her little son, requesting for some of her time to answer a few basic questions. She was gracious and scampered away asking us to wait, in order to pull out a couple of chairs from inside one of their homes. The walls and roofs of these homes were made of tin and roofs covered with tarpaulin. We told them that chairs were unnecessary and we could talk to them standing, but she desisted only after being unable to find the chairs she was looking for after looking inside two of their homes.

Over the years, the number of shanties behind Palash Nivas, or OBH as it is popularly called, has seen a gradual increase. After the construction of the new girls hostel was completed, work on campus has been limited and a number of shanties are now unoccupied. There are seven shanties each housing families of four.

The people living in these shanties are the invisible people of IIIT. They exist, but only in the shadows. We see them sometimes, but never really notice them. That there are shanties behind OBH and are occupied by people may come off as a surprise to many.

“It was scary when we first came here. There were snakes, mosquitoes. No proper place to stay. But now we are used to it,” says Saraswati. She tells us that cobras are spotted often. But they are used to it, even with her son—who must not have been more than four—scurrying about on his small plastic cycle toy. “Wild boars are also spotted sometimes… one was right here, the other night,” she says, pointing towards some of the homes further in.

Saraswati’s family and the other families living in the shanties work as labourers in construction. Before coming to work here in IIIT, they were agricultural labourers back home in their native villages. They are all from within Telangana, some of them from the adjoining Medak district. Men and women both work in the construction on campus. However, with less work these days, the women were staying at home while the men did the working. As daily wage labourers, it was apparent that this meant a substantially reduced family income.

By now, a number of women have congregated next to Saraswati. She says that she has been here for three or four years now. One of the very few men around also gets involved and says that he has been here for seven years. Most people have been staying here for three to four years, though a few have come as recently as three months, and some others were here for a while but left as the availability of work on campus decreased.

Once the man joined in, the women were visibly quiet unless specifically addressed. The man took over the conversation, before attending to a call and leaving for work.

They have a bathroom with water access provided by the institute. However, they say that it was only built a year ago. Before that they did have bathrooms but with no water access. It is no surprise, then, that they preferred to go “outside”. In other words, out in the open in the adjoining forest area. Any early lark who has lived in the E-Block of OBH before a couple of years, will tell you about the daily sights of people uncomfortably squatting in the bushes with a mug in hand. The mud path that leads from OBH to the faculty quarters would then become unusable on account of the consequent stench.

Drinking water is accessible through the water cooler in OBH. They use old Bisleri water cans in order to have their fill whenever required.

The houses with their tin roofs can get especially hot in the summer. They have electricity access through OBH, they say, pointing towards a lone insulated wire which seemed too exposed to be safe. Most houses have fans. Stand fans—not ceiling fans—but three families don’t. “They are yet to buy them,” they say. Very few, about two or three families, also made use of desert coolers in the sweltering summer heat. But neither fans nor coolers or other appliances such as light bulbs were provided to them and had to be bought.

Even though they all have Aadhaar numbers, they seemed to be unaware of the government’s Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana (PMUY) which would give them access to LPG cylinders. They used firewood collected from the adjoining woods in order to cook, some of which they had stored under a shed right next to where we stood. Apart from being inconvenienced, women are the primary victims of the negative health consequences of firewood smoke, which they are directly exposed to while cooking.

In addition to the limitations that they have to how they cook, what they cook is limited by the lack of access to fresh vegetables and the unavailability of refrigeration. They get their vegetables once a week from the market in Lingampally, which is 8 km away. Due to this, they consume more of vegetables which do not spoil soon, such as potatoes and onions.

Health issues crop up every now and then. Mosquitoes are a major problem. They would often request security for the regular fumigation that the rest of the campus frequently undergoes, but little heed would be paid to their requests. One of the men once got malaria, for which he had to be admitted, first to a government-run, and later a private hospital. Minor fevers are much more common.

The residents of the shanties do not have any institutional health support. They have to run pillar to post for any ailment, big or small. They have only the one point of contact with the institute, Mr. Srinivas Goud, who they say has been quite helpful in the past. He has given them rice and sometimes money when required for a special occasion, but he could not help them get access to even a rudimentary healthcare service on campus. They lamented this lack of a “health card” which they could use. Mr. Goud, on his part, does not seem to be a permanent staff member of the institute and may not have the awareness of Aarogya or the authority to allow them to use it. This results in the exclusion of perhaps those who need the services of basic medical aid the most. Construction workers are susceptible to injuries and inhale concrete dust which further causes health issues, both in the short and long term.

Housing for construction workers has been managed exceptionally by IIT Gandhinagar, who back in 2014 got a Housing and Urban Development Corporation (HUDCO) award for “Best Practices to Improve the Living Environment”. Times of India reports, “IIT Gandhinagar ensures dignified and sanitary housing conditions for construction workers by including special conditions in all its contracts that obligate contractors to construct clean, hygienic and well ventilated workers’ housing with adequate water supply, electrical and sanitation facilities.” They quote S K Jain, the director of IIT Gandhinagar, saying, “We aspire to prepare graduates who are sensitive to societal needs. This cannot happen if the institute does not exhibit its own strong commitment to the less-privileged members of our community.”

Saraswati and the others may have migrated to Hyderabad in order to work and earn their livelihood, but they say they preferred it back home where the least they had were pucca houses. For now, they make do with visiting whenever there is a festival approaching.

* name changed

(The author thanks Sraavani Gundepudi for her invaluable help in interacting with the residents.)

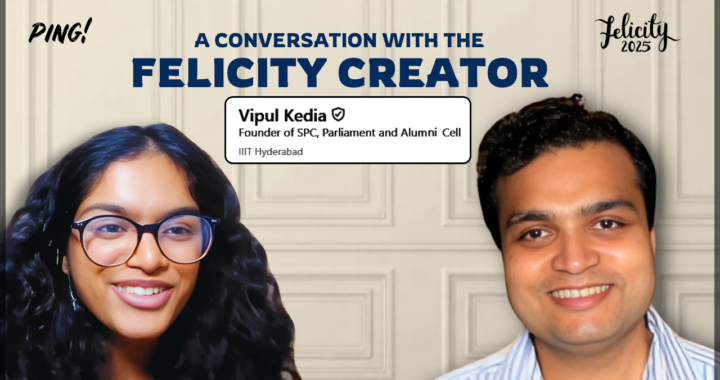

Vipul Kedia on building Felicity | The story of how it all began…

Vipul Kedia on building Felicity | The story of how it all began…  Cleaning up the Mess?

Cleaning up the Mess?  The Mess-y Situation

The Mess-y Situation  Qu’ils mangent de la grenouille! (Let Them Eat Frogs!)

Qu’ils mangent de la grenouille! (Let Them Eat Frogs!)  Tale of Two Cheenties

Tale of Two Cheenties  Log Kya Kahenge?

Log Kya Kahenge?  Can you hear the music?

Can you hear the music?  The river of time

The river of time