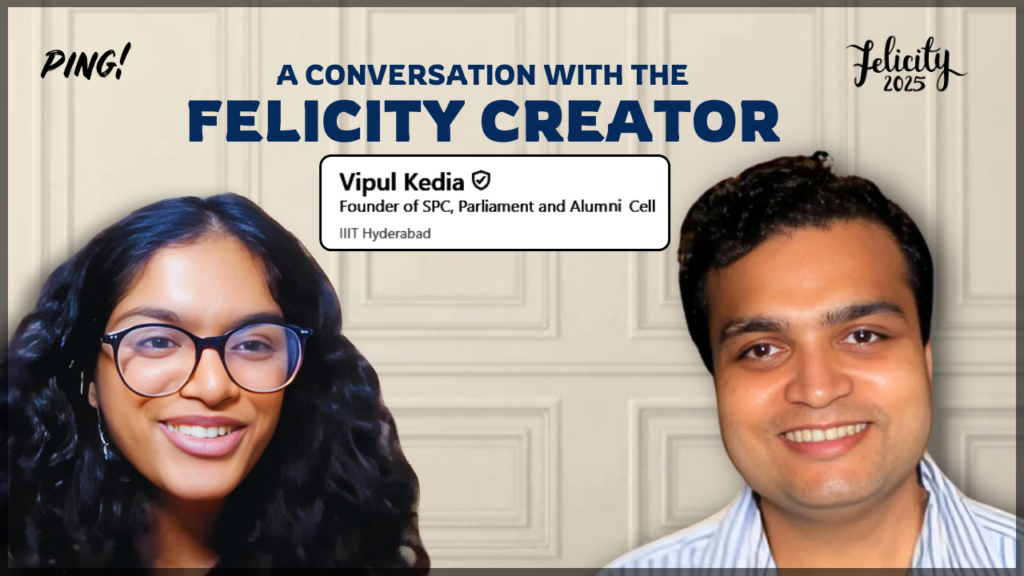

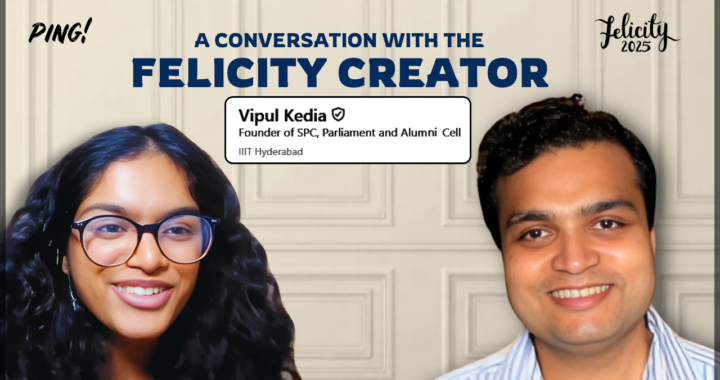

Vipul Kedia on building Felicity | The story of how it all began…

In collaboration with Felicity, we bring to you an exclusive conversation with Vipul Kedia, alumnus of the 1999 batch and the first Felicity coordinator, organised back in 2001. A B.Tech (Hons) graduate in CSE from IIIT Hyderabad and an MBA from IIM Ahmedabad, he now serves as the Chief Data & Platforms Officer at Affle. Both during and after graduation, Vipul has contributed massively to the IIIT we see today. During his time at IIIT, he organised the first Felicity, was a part of the Student Parliament and helped organise some of the first placement rounds on campus. Post graduation, he played an integral part in setting up the Alumni Fund, as well as serving on the Governing Council of IIIT as an observer member.

As Felicity counts 25 years of existence, Vipul shares insights into the origins of Felicity, his journey as a student leader, and the legacy he helped build. You can watch along!

[Vaishnavi]: As I’ve read from articles and heard from people in the college, you have been very involved with the college. Even in your time here, you were very involved with the Student Parliament, Felicity, etc. And now you’re very involved with the Alumni Association and the Alumni network. What drives you to be so involved with the college? What is the motivation for all of this?

Vipul Kedia: I think more than anything, it’s the feeling of belonging.

When we joined IIIT, one thing you all have to imagine, because it’s difficult for you to understand, is that we had taken a huge amount of risk. At that time, IIIT did not have a deemed university status. So, we had taken the risk of joining an institute which was just coming up: without basic infrastructure; without faculty; without even the certainty if we would get a degree at the end of our graduation. So when you are stakeholders in a venture, to give you a startup analogy, you automatically do a lot of things which, you know, in a normal scenario, people would not do. You are equal participants in making sure that the venture becomes successful.

The second factor, which I think played a role, was that for our entire first year, there was no faculty on campus. They were just visiting faculty, borrowed from here and there. There were a few faculty members who continued for a long time, like Professor Kaul, Professor Govindaraju, etc. But none of them were staying on campus at that time. When you are left independent, and when you have to do everything that’s supposed to be done, and there is nobody who is going to do stuff, automatically a lot of initiatives come on.

The third factor was that, when you start growing with a venture, when you start growing with the institute, there is that sense of belonging. All the faculty that you see today, most of the senior faculty joined towards the end of our second year. So Professor PJN and Professor Jawahar, Professor Kamal, Professor Jayanti, Professor Vasu, all of them joined during our second year, third year, etc. So when they came in, it was as if we were welcoming them to the institute. And they continued to make us feel like equal stakeholders because even they were trying to find their footing and getting settled into the institute. It was us, the students at that time, who had to play that role of helping them settle in, while also playing stakeholders to defining what IIIT was going on to be, and set in place many, many things like, you know, Felicity itself or the student parliament or first placements and so on.

So when you are involved with something from such an early stage, automatically, you have that sense of ownership. And that is what drives you, because whatever you start at the age of 18 (or) 19, you always have a certain fondness for it; a certain want for it to succeed. When you want something to do well, and you see a scope to contribute to that, you continue doing that. I think that is what it is, personally, for me and many of the other early-batch alumni.

[V] That is actually wonderful. I can’t imagine being like someone who was 18, seeing a situation and saying, I’m going to build this up. And I think that kind of initiative taking is honestly very commendable. It attests to the standard of the college even now, because even now we have very good relations with our professors, they’re open to communication and I think that culture comes from like that time when you all did it for us. How do you manage your time with curriculum and extracurriculars?

Vipul Kedia: I personally always believe that time is expandable. Whatever you want to do, you will always do, and you balance and decide how much time to devote to it. As far as I was personally concerned, a lot of other students were devoting a lot of time to learning different technical skills. Obviously, I did not do as much as what some of the others were doing, because I was trying to build a lot of other things and devoting a lot of time to the extracurriculars and so on.

But honestly, I mean, time management and all of those things, those were not terms which were possibly coined 25 years back and nobody used to think of it that way. It was that you have to do something so you have to do it. If you have to stay up all night to plan something and execute it, you will do it. And even, initially, the professors were also very accommodating. I remember telling a professor that I couldn’t attend your class because I had to plan something for Felicity, or plan something for placements, and that was a valid excuse. Professors would allow you to do that because they knew that some of these things were important at that stage. Those were also equally important for the foundations of the institute, and we were doing things very sincerely and in a committed manner. I cannot give any secret sauce or anything. When you are passionate and happy doing something, then you never feel that sense of time or the stress of going the extra mile. I think that’s what it was.

[V]: That is very nice. I mean, I do see it also with people who continue on college culture. You see that a lot of what it takes is passion. It’s like going away from the grain and doing something you care for.

Vipul Kedia: It is all about passion and I think nothing more. Passion is what drives it, and if you’re passionate about something, I think all of us for different things, we lose the sense of time and we lose the sense of effort when you are doing something which you really love and you really associate yourself with.

[V] Yeah, that’s honestly pretty beautiful.

The next question is more related to Felicity itself because like this entire conversation is for Felicity and considering that it is the 25th year of it running, we wanted to see like what made you want to start Felicity? What made you want to start the culture of having a fest? What was the initial idea and what did you envision your fest to look like at the time?

Vipul Kedia: It was honestly just a thought, for a couple of years before we started Felicity. I wouldn’t say in (19)99, but in 2000, primarily and in early 2001, we used to have some inter-house activities. We always had a place marker in the almanac for the cultural fest. It was just called the cultural fest or some similar term, and it just struck us, why not expand it? I had that thought and I spoke to a few others in my batch and my senior and junior batches, let’s do an inter-college festival, let’s expand our horizons. We obviously knew about all the IIT festivals and all the local Hyderabad festivals which used to happen in other universities.

We were cut off at that time from the external world, because we are still talking about a time when Indiranagar used to be a hamlet. There was no ISB. That entire road which you have beside IIIT, that was all a jungle, and beyond IIIT was also a jungle. After IIIT, there was Hyderabad University and Gachibowli was practically nonexistent. It used to be just a few small shops in Indiranagar, like a small village. We did not really know what was happening. We did a lot of things: created some basic brochures on Word documents, printed some basic stuff. Some students at that time were from local junior colleges, so they went around doing publicity.

It was just being ambitious and thinking of doing something out of the box, and then just planning it along the way. Thinking, oh how do we get the money, or how do we get some cultural performances, how do we divide ourselves into teams, who takes care of the cultural events, who takes care of some of the tech events, who takes care of entertainment sponsorships, event planning, execution, all of that. Just a few dozen excited students coming together and getting the blessings of the faculty and then setting out onto our own journey.

We went to one of the faculty members who used to teach us English at that time, Professor Sudhakar Marathe, and I was on very good terms with him. I said, we are doing a festival, what do we call it? He came up with the name Felicity, and sent me an entire email with the explanation of what Felicity should be about. His vision was relating back to society, not just a blatant celebration of fun, but also a socially aware celebration. That is how it started: just enthusiasm, just initiative, and just the want to create a mark to create something which becomes the focal point of student life in the institute.

[V]: Could you expand more on what the professors and your own vision of Felicity was like? And when you say socially aware, what do you mean by that? what is the driving initiative behind that?

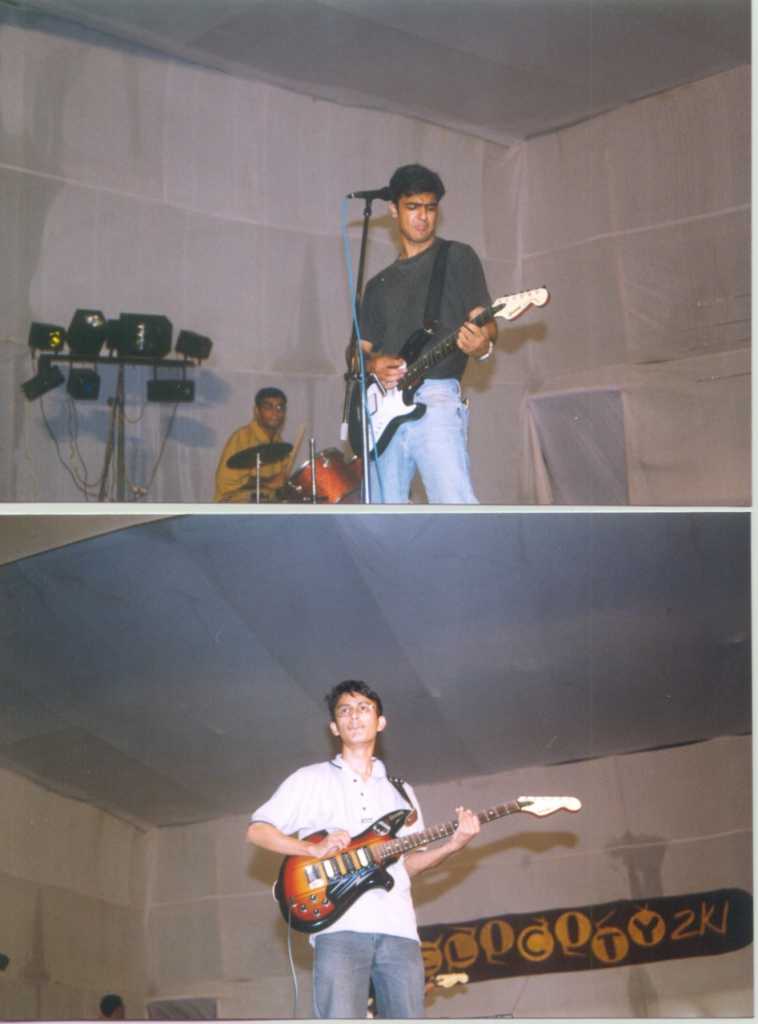

Vipul Kedia: One thing then was that most college festivals were all about very loud bands, very loud music, and having a lot of fun. There were obviously talks of people getting drunk and things like that, so it was more like a party in the name of cultural festivals.

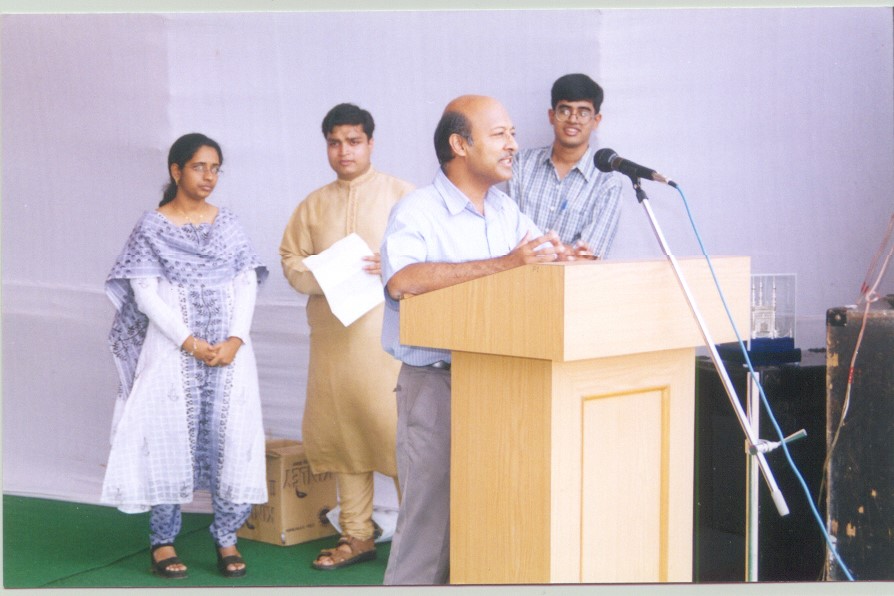

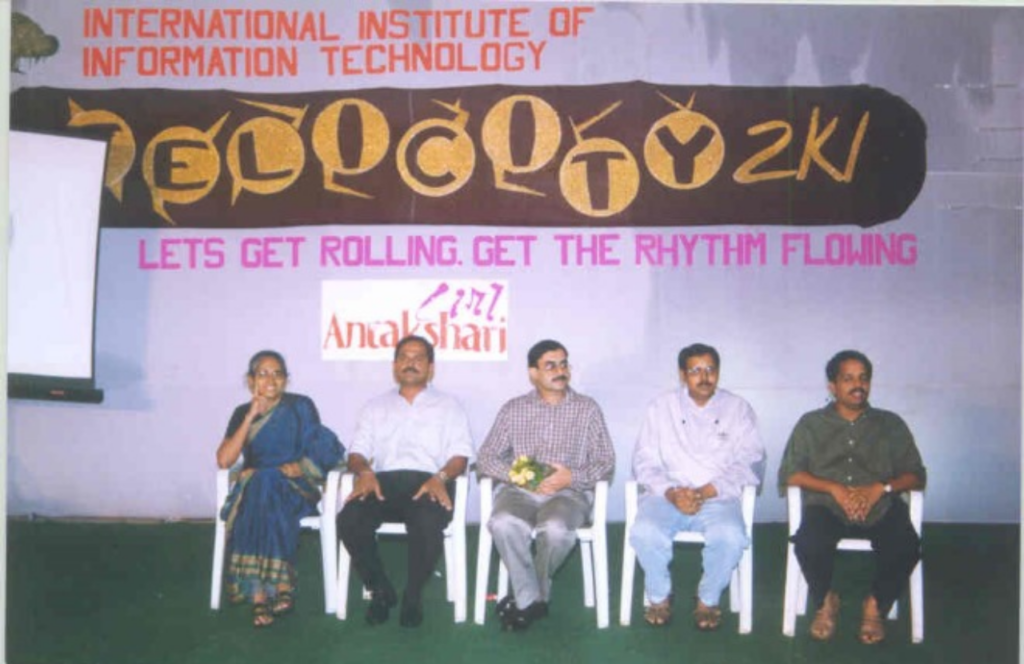

How was Felicity different? The inauguration was a classical dance in Kuchipudi by Padma Shri Dr Sobha Naidu. Instead of a regular DJ night and the likes, there was a Dandiya night which we did, then on the third night obviously we had a band that performed. There were more classical cultural celebrations.

We also had involvement from all parts of the institute, right from the staff, to the faculty, and the students. The main message that Professor Marathe wanted to send out with the name was that it is not just a celebration of fun and privilege. Rather, it was that these are a bunch of students who are aware of the larger society around them, and they want to celebrate and have fun, but at the same time not do it in a garish and ostentatious kind of manner. The idea was that it is a sensible festival, well-grounded, where the students are themselves taking initiative, planning and executing a lot of the events and not just taking sponsorship money and spending it all around.

The budget of the first Felicity was hardly around four to five lakhs, where each student put in 500 rupees. The institute also put in an equal amount of money, and we got some small sponsorships, about a lakh or something, plus some money from the stalls. When you are yourself contributing money to the festival, then it becomes a co-owned initiative, and that is where some amount of social awareness also comes in. Because, when you’re putting in the money, you will not waste the money. You will realize the worth of the money.

Those are some of the things that set Felicity apart. It wasn’t just partying and fun, it was a festival for the entire community, including the staff, faculty, and the students.

[V]: It seems to be like Felicity at the time – and even now to some extent – is like a very collective fest within IIIT. I assume, considering that IIIT was even smaller then, as compared to now, that the fest was very community driven.

Could you elaborate more on the community-drivenness of felicity itself? How did you pitch your idea to other people? How collaborative were the professors? How involved were they? Did they perform, for example?

Vipul Kedia: The faculty was very involved. When we went and spoke to them, saying we are planning to do something, we need budget and support, the faculty was wholeheartedly willing to do that. They gave us everything that we needed. They gave us the budget, they gave us the flexibility to work for it. They were fully involved in terms of giving us the connections, helping us connect with the other institutes, getting some of the performers, and most importantly I think being our backers. Because it wasn’t that the faculty was inhibiting in any manner, rather, the faculty was always there to support. Even if we wanted them at midnight for something, they were always available to go on, to plan, to discuss our ideas, to help us refine what we wanted to do, and so on. It wasn’t really pitching or anything, it was more in terms of just sharing the idea and everybody wholeheartedly accepting the idea, because I think it was you know something that was waiting to happen.

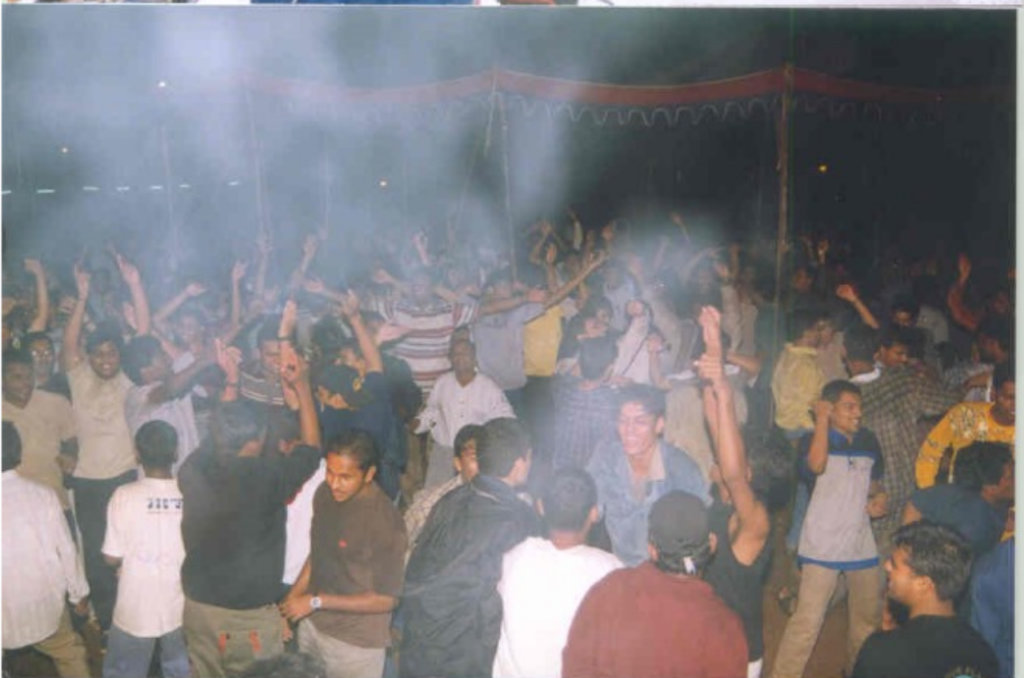

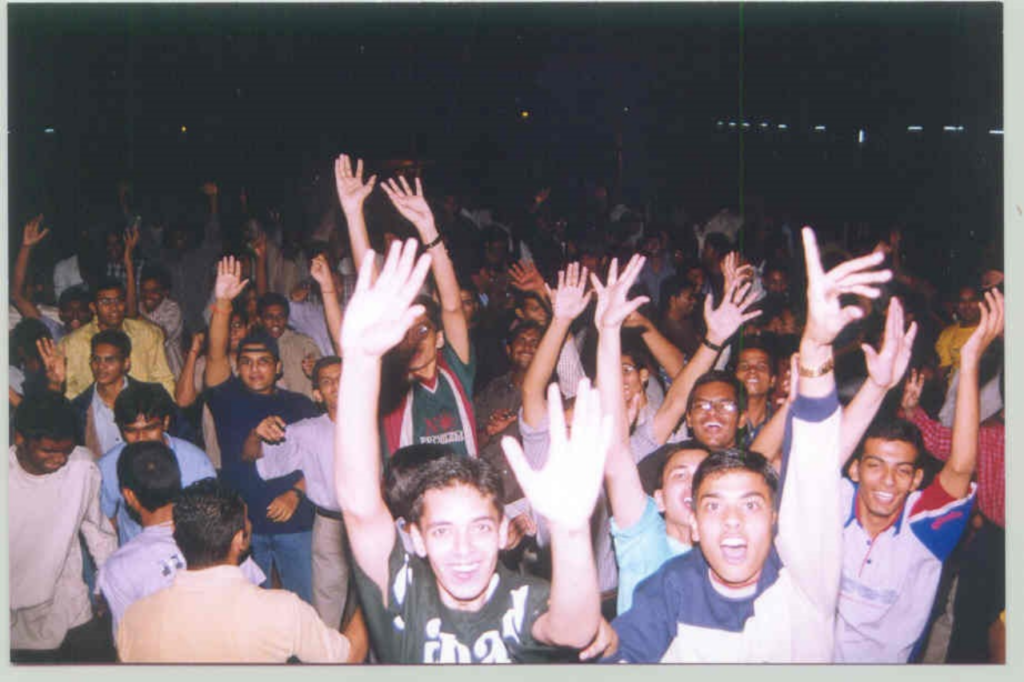

I remember Professor Jayanti, who used to be our SLC chair at that time. After Felicity, she sent out an email, saying that this was like the coming of age of the student community, where people could come together to make it happen. (On the) last day of Felicity, actually with the permission of Professor Jayanti, we designed T-shirts for all the team members (about 70-80 people) who were involved in planning and executing Felicity, as a surprise. Nobody else knew it, except for me and Professor Jayanti, and it was a simple t-shirt with “Felicity – I made it happen” on it. That was really a proud moment for everybody, to wear that T-shirt and go around and feel that they have created something special together — having that sense of ownership. I think that is how the community came together and how it paved the way for almost all the other cultural events.

[V]: I just realized the scale of the events back then, and we still have that culture from your time. I think I’m grateful for it and I can’t imagine the level of happiness that would be like present during that especially when you surprise everyone with a different feeling.

Vipul Kedia: I think it was also a function of the time then. In today’s times, it is very difficult for it to happen. You have to also imagine the time when there were no cell phones, there was no laptop, it was all wired internet. You really did not have much to do. I mean what do you do sitting on campus? You plan things, you execute things, you come together, you do something. Unlike today, where you have the option of just sitting in your room, and, you know, watching content or interacting with your friends or whatever online. So when you are in an offline world, that has inherent advantages, because everybody is really thinking more, talking more, interacting more, spending more time together and that is where collaborative initiatives can come through. In today’s time, I don’t think it is very possible because most of the students will be involved in themselves, on the internet, with their laptops and mobile phones.

[V]: Right yeah, that makes sense. Apart from the T-shirt distribution thing, is there any special memory that stands out in Felicity? Was there a moment you realized that, “Wow, I built this, I helped to execute this”?

Vipul Kedia: I think when you look at things in hindsight, they are always more glamorous. But honestly, at that point in time, you have to imagine, we planned it in three weeks, from the day of initiation to execution. It was just, you know, realizing what needs to be done, and going and doing it. And then every night, coming together, sitting in CR5, at that time, and discussing who has done what in the entire day, what have been the learnings, what have been the accomplishments, what is it that we need to accomplish on the following day. So you didn’t really have time to think. I obviously had a vision of what we should do, but there were no benchmarks. We were setting benchmarks as we went along.

It rained on all three nights of Felicity, and it was the first experience in crisis management. The Dandiya became a Rain Dandiya, and the band performance became all messy with the muck in the fields and so on. You were just doing things, and you really did not have any time to sit back and think about what has happened or what you accomplished. It is only in hindsight, and when you look back at it after all these years, that is when you realize why what happened was special. At that point in time, we did not even possibly know that it was anything special, for all it mattered. It seemed to us that everybody else was doing it, and we should be doing it. We did not really see ourselves as being the founders of something, it was just done for fun, enjoyment, and enrichment of our own lives.

When we look back today, obviously, you feel very proud, that 25 years have passed on and the tradition has lived on and now you can feel that you know we were the founders and you know, I initiated this and that. But at that point, we are young kids and you’re just living today. You’re not really thinking about what you’re doing for the future.

[V] I mean like as a follow-up to that; my question to you is- what do you want to see in the future of Felicity, what would you like to see in the fest again? Have you attended any of the previous fests?

Vipul Kedia: No, I haven’t been able to attend any Felicity since I passed out, and I would love to do that.

But I think the most important aim of Felicity was to bring the student community together. One thing that causes me a lot of pain, which I hear from faculty, the Felicity teams, and the SAAC teams, is that a lot of people do not attend Felicity. They go out as groups to Goa or some other place, for celebration, and I think it is a big miss. You are talking to me today because we did something 25 years back. You would not be talking to me today about a trip to Goa 25 years back and how much fun we had with our friends.

You do not realize how many things these experiences teach you. They are the first exposure that anybody has to team building, to organization, to collaboration, to coming together, to executing a task, problem-solving, uncertainties, planning, execution, budgeting, finance; there are so many nuances to it. And when you are tackling a complex problem together as a large group of 70 or 80, you do not have these opportunities in your work life. You do not ever have these opportunities once you graduate. If you miss out on those experiences then you’re really missing out on an important part of being a student and an important part of learning.

So, Felicity is not about a particular event, competition, band or what you are doing. It is, finally, what Professor Jayanti put very aptly in one line: the coming of age of the student community. It is students collectively realizing what they can achieve and what they can do if they work together, the power of teamwork, the power of collaboration, the power of camaraderie. I mean, I am today connected across so many batches. Pretty much every batch I’m connected to someone. The first five, six batches, everybody knew me, even after I graduated. The reason for that is because we did something together, we built something together, we executed something together, and those are the relationships which carry. That is the only thing which I hope Felicity keeps on accomplishing, that it allows people to come together for a large initiative, which nobody individually can do or nobody will get the opportunity to do once they graduate from college. It helps build the student community, it helps build the student body, and it helps people gain these valuable experiences, which will hopefully help them much beyond just the technical skills that they gain in the institute once they graduate.

[Responses have been edited for clarity and length]

Addendum: Professor Sudhakar Marathe’s email

[Editor’s note: Vipul Kedia kindly shared the email that (now, Late) Professor Sudhakar had sent him when he had requested Prof. Sudhakar for a suggestion for the name of the cultural fest. We have reproduced it in its entirety for your perusal.]

FELICITY.

THIS SHOULD ALSO FIT AN ON-GOING ACTIVITY, FOR INSTANCE A ONCE-A-YEAR AFFAIR (OR FAIR!), EVEN. AND IT IS A CALMING WORD AS OPPOSED TO SOME WHICH ARE BOISTEROUS AND CLAMOROUS!

I DO BELIEVE THAT, BECAUSE ALL OF YOU WITHOUT EXCEPTION ARE SO EXTRAORDINARILY PRIVILEGED, COMPARED TO A COUPLE OF BILLION PEOPLE ALL OVER THE WORLD, YOUR FIRST GESTURE IN THIS (AS, INDEED, IN ANY SUBSEQUENT) CELEBRATION SHOULD BE TOWARD THOSE WHO ARE LESS PRIVILEGED THAN YOU–AN OPENING STATEMENT, A COMMITMENT TO MAKE THE WORLD BETTER THAN YOU FOUND IT

THIS COMMITMENT COULD EVEN GO ON ALL YOUR PRINTED MATERIAL, AND INITIATE THE FIRST SPEECH OR DECLARATION OF COMMENCEMENT OR INAUGURATION OF THE FESTIVAL. NONE OF YOU IS WHERE HE OR SHE IS BECAUSE OF ANYTHING YOU DID–THE WORLD HAS MADE YOU AND GIVEN YOU THIS NICHE. (AND IT MAY ALSO PLEASE THE “AUTHORITIES”!)

ACKNOWLEDGE IT FIRMLY AND HANDSOMELY AS I HAVE SUGGESTED. OTHERWISE YOUR FESTIVAL WILL END UP BEING A BRASH, AMERICAN STYLE, CONSUMERISH, ARROGANT SHOW OF PRIVILEGE WITHOUT ANY AWARENESS OF THE CONDITION OF THE REST OF HUMANITY.

HOPE THIS WILL MAKE YOU REASONABLY HAPPY.

SINCERELY,

SUDHAKAR.

Qu’ils mangent de la grenouille! (Let Them Eat Frogs!)

Qu’ils mangent de la grenouille! (Let Them Eat Frogs!)  Tale of Two Cheenties

Tale of Two Cheenties  Peace of mind.

Peace of mind.  Boats and Valorant

Boats and Valorant  Blessings

Blessings  Shivering in the sunlight

Shivering in the sunlight  Vipul Kedia on building Felicity | The story of how it all began…

Vipul Kedia on building Felicity | The story of how it all began…  A perspective on sports in IIIT

A perspective on sports in IIIT  Paintings of IIIT

Paintings of IIIT  The Tale of Jagruti

The Tale of Jagruti