Commentary on Disciplinary Committee Decisions

The file that is being referred to in the following article was circulated in an email by Appaji.

The apparent prevalence of academic malpractice in IIIT is very concerning, though it is not a problem confined to our institute alone. To be convinced of this, we need only look at Insight’s Senior Survey, where 53% of final-year students in IIT-B admitted to having committed malpractices in the past [note] http://seniorsurvey.insightiitb.org/academics.html [/note].

An e-mail was recently circulated with an enumeration of disciplinary cases and the corresponding consequences. Firstly, we would like to applaud the decision to make this public – more transparency in such matters is very welcome, and we also understand and support the motive to discourage further such incidents. However, the document is afflicted by inconsistency and ambiguity.

First of all, the decisions made have several concerning aspects. For example, it seems extremely harsh to penalise 50% of the marks of an exam just for writing after the bell. Also, it seems that an F grade has been given for bringing an additional sheet to the the exam. Now, it is unclear what this exactly means. Let us assume the most reasonable interpretation, that it was a sheet containing notes. But that raises another question: why were the students who brought handwritten slips given Fs for all the courses of the semester? We fail to see a difference between the two cases that warrants such a difference in the disciplinary outcome. So it seems that something is wrong here, irrespective of how one chooses to interpret the case description.

Another issue is that talking to each other during the exam apparently attracts a penalty of a grade drop. This is in contrary to the decisions for all other exam-related malpractices, which either have straight Fs in courses or reduced a  percentage of the exam score – therefore, for minor malpractices that don’t warrant an F, the punishment is tempered (or magnified) by the exam’s weight in the overall grade of the course. The more the exam matters, the worse the punishment is. Except, apparently, if you talk during the exam. In that case it’s a grade drop – totally independent of the pattern followed in every other case of cheating in exams! If you write past the bell, it is a 50% reduction in marks. Most instances of copying are given a 0 in the exam, or F in one or more courses. But for talking, it is a grade drop? Why is it that the consequences for talking in an exam are independent of how important the exam is, when that is the pattern that has been followed in all other cases?

percentage of the exam score – therefore, for minor malpractices that don’t warrant an F, the punishment is tempered (or magnified) by the exam’s weight in the overall grade of the course. The more the exam matters, the worse the punishment is. Except, apparently, if you talk during the exam. In that case it’s a grade drop – totally independent of the pattern followed in every other case of cheating in exams! If you write past the bell, it is a 50% reduction in marks. Most instances of copying are given a 0 in the exam, or F in one or more courses. But for talking, it is a grade drop? Why is it that the consequences for talking in an exam are independent of how important the exam is, when that is the pattern that has been followed in all other cases?

Speaking of inconsistencies in decisions, something else that we find troubling is that a person found copying from his phone in the exam was given an F in the course; a person repeatedly caught copying from their phone had to repeat three courses; but an even higher punishment – an F in every course of the semester – is apparently reserved for those who brought handwritten notes to the exam hall. Evidently, bringing handwritten slips is considered to be a far worse transgression than copying from a phone. Why this is so is beyond me. In general, there seems to be very poor cohesion between the committee’s decisions in different cases. The notion of common law seems to be totally lost on them. Different cases of cheating having similar severity seem to have wildly varying severity of consequences. Not only that, but even the parameters of punishment seem to vary – sometimes the weightage of the exam affects the punishment, and sometimes it doesn’t, in what seems to be a totally arbitrary fashion. There is seemingly no overarching policy in place. Not only that, but it doesn’t even seem like there are any general working rules being followed here.

Apart from the decisions themselves, the document is not presented in the most optimal manner. In other words, the document isn’t very well written. In many situations, it is difficult to make conclusions without more details in the case description. For example, what is meant by saying that a student added four additional sheets to the answer booklet? Again, let us assume that they were pre-written sheets; then it again seems absurd to get an F in all courses of a semester for bringing handwritten slips when bringing four whole sheets gets you an F in that single course. The point here is that those who brought handwritten slips seem to have been given disproportionately worse punishments compared to other similar offences.

The issues pointed out so far have mostly been mismatches in punishments between cases, and unclear case descriptions. These are bad, no doubt, but the Byzantine policy for Proxy Attendance is a whole different story. The person giving attendance gets three grade drops in the course in which they have the lowest grade. Note that getting an F is much worse than getting a D – the course will have to be repeated, and no credits are earned. Apparently the committee has decided (for some reason) that giving proxy attendance when you have at least a B- in all the courses in which you don’t have an F is a far lesser offence than doing the same thing when you have a C, C-, or D in some course. Yes, it is quite a strange and convoluted criterion. We are unable to contrive a thought process that could formulate such a set of criteria. The punishment need not just fit the crime, apparently – it depends also on the precise configuration of grades you have in the current semester.

Upon inquiring with a senior student involved with the academic disciplinary committee, we discovered that the institute deals with these disciplinary cases on a case-by-case basis, and the final punishment depends on how the student presents his case, a “personalised punishment”, if you will. Firstly, it would be very helpful if this was included in the document itself. However, in this case, it becomes fruitless to read punishments removed from their context. The purpose of circulating such a document should be to make it clear that certain offences attract certain punishments. However, we are unable to derive any such information from the document as it is due to a lack of information on the variables involved in the decision-making process.

discovered that the institute deals with these disciplinary cases on a case-by-case basis, and the final punishment depends on how the student presents his case, a “personalised punishment”, if you will. Firstly, it would be very helpful if this was included in the document itself. However, in this case, it becomes fruitless to read punishments removed from their context. The purpose of circulating such a document should be to make it clear that certain offences attract certain punishments. However, we are unable to derive any such information from the document as it is due to a lack of information on the variables involved in the decision-making process.

However, having pointed this out, we still strongly believe that some of the inconsistencies in punishment are beyond what can be explained by this. Does the institute take precedence into consideration at all? Are there any basic working rules that are followed, or are these “personalised punishments” simply dependent on how they feel about each student and case?

In conclusion, we’d like to reiterate that while deterring malpractice is vital, more thought should be given to having common standards for decisions on similar offences. If not that, then at least, some basic working rules, so that the discrepancy between punishments for similar offences does not grow too large. Most importantly, It would be good to consider what the parameters of the punishment are – what factors temper or magnify the effects of the decision, and are they the intended parameters? Should those parameters change the severity of the decision?

It would also be worthwhile to have more clarity in conveying these decisions to the community. The document is filled with ambiguity, making it difficult to understand the exact nature and circumstances of the misconduct. As a result, reading the document proves to be an unenlightening activity. Perhaps a more descriptive document could help us achieve better clarity. This would help all of us move towards better academic standards and transparency.

Cleaning up the Mess?

Cleaning up the Mess?  The Mess-y Situation

The Mess-y Situation  Qu’ils mangent de la grenouille! (Let Them Eat Frogs!)

Qu’ils mangent de la grenouille! (Let Them Eat Frogs!)  Tale of Two Cheenties

Tale of Two Cheenties  Peace of mind.

Peace of mind.  Can you hear the music?

Can you hear the music?  The river of time

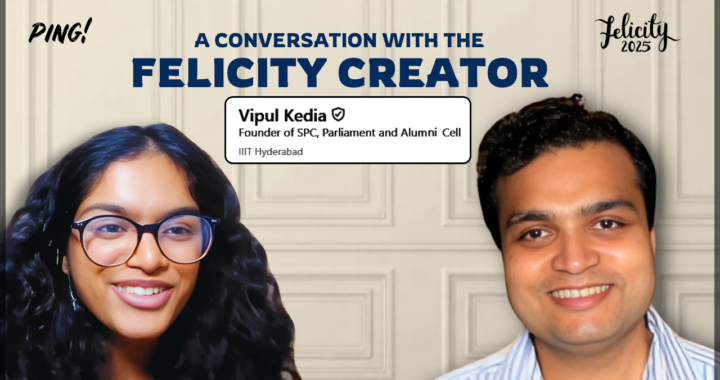

The river of time  Vipul Kedia on building Felicity | The story of how it all began…

Vipul Kedia on building Felicity | The story of how it all began…